To lend a little breadth to the short shorts presently posted in OPEN:JA&L—four from my jail time, three from a collection off-Bible stories—, I thought I’d include some variety here.

Variable

They do it all right in the office, the doctor said. The anesthesia, and a muscle relaxant called succinylcholine, and whereas there once was a 36% chance of cracking vertebrae, especially the fourth lumbar, or certain back teeth, nowadays the risk is negligible, less than one-tenth of one percent. Oh, and the really interesting thing—showing me on my own temples—is that the current is variable! Yes, the amount to induce convulsion is specific to the patient! All the way from 25 to 2000 volts!

His voice is so excited you’d think he were perched one cheek on each of his electrodes. I watch him in his priestly white, the acolytes helping my wife remove her shoes and any hairpins.

Up on the table, click click click they snap tight the anklets and a cinch while accustomed professional fingers align what they nowadays professionally call the head.

It gives one pause, they move with such dreamy alacrity, like an irreversible thing—dash, dop, the paste on the temples, the headband fitted, and, looking like nothing so much as an orthopedic jock strap, the gas mask glides in.

The juice.

Her eyelids flutter, I feel such tenderness. I will gather that smithereen of memories, sort them, keep them safe, someday maybe grow another wife around them.

[ ]

Published in: ¶ A Magazine of Paragraphs, 2003

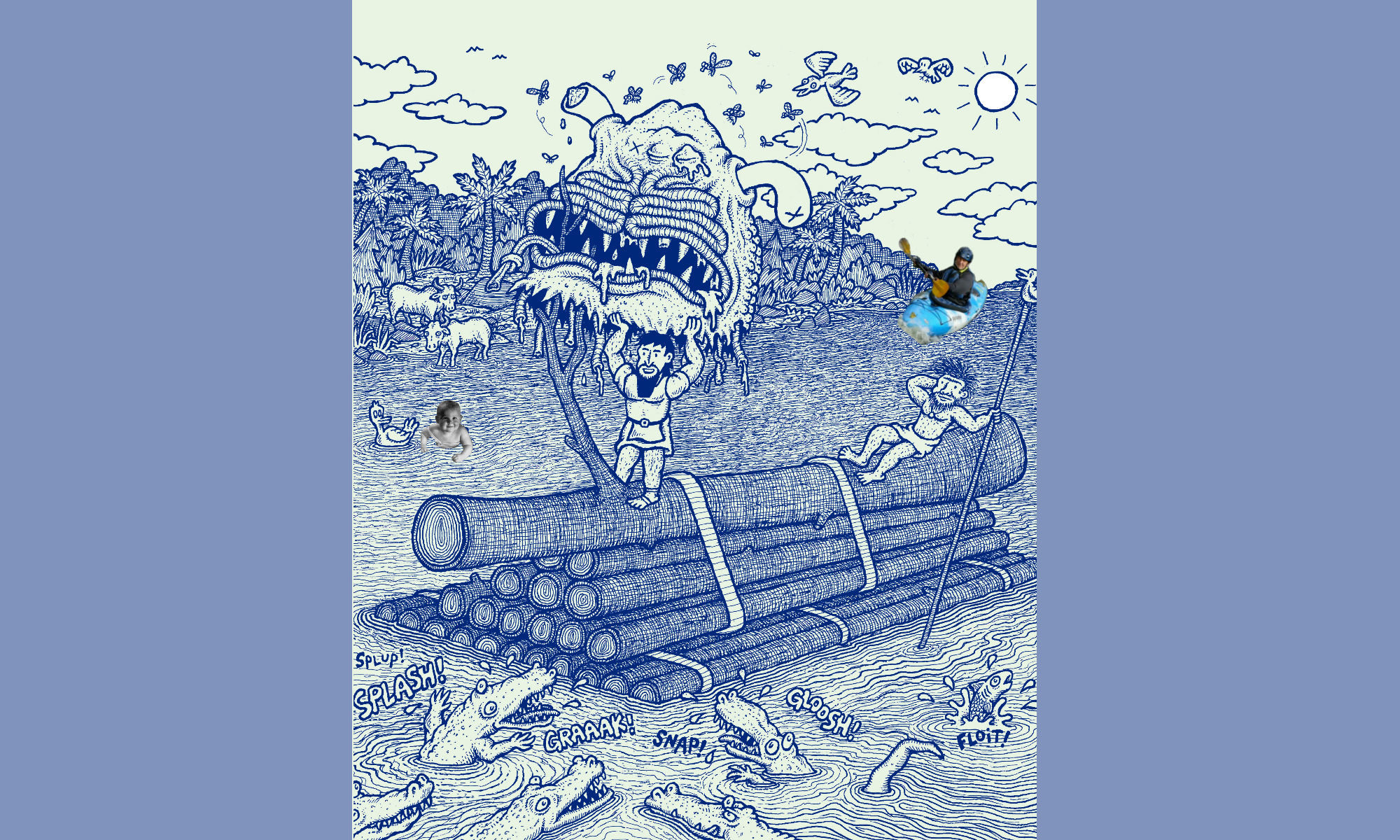

AY, A COUPLE OF YAKS IN A KAYAK

A Y

K A Y A K

K A Y A K A

K A Y A K A Y A K

K A Y A K A Y A K

Y A K A Y A K

A K A Y A K A K

K A Y A K

Y A K A T Y

A

K

Note: How many yaks can a kayak yak, if a kayak could talk back?

A Kafka Story

I dream I am translating a short work by Kafka. It’s one of his simple things—a man and a village and a mere handful of sentences amounting almost to a sweet reminiscence, as run through a Chagall-like bucolic vertigo, except of course one is also anchored by the underlying voice within the voice, those murmurs of ineffable guilt, undiscovered loss, chortles like hoarse starlings strutting beneath a backyard gibbet, and I keep smoothing it over, bringing forward the distant children’s voices, adjusting words and rhythms and the ominous, lonely, airy float of it until I’ve got it perfect.

And then I force myself, in my dream, to go over it some more, line by line until I have it memorized. It is perfect. Franz himself would pause, might even smile, a glimmer in those cavernous crow’s eyes at least. That’s as far as he would go, but still, it would be our fleeting moment, that I would cherish forever.

And then, I wake up.

Quality Time

by

Kent H. Dixon

For Renée Barat Fannon (1916-2006)

One last gasp like she was catching her breath and then she altogether stopped.

—Wow, Mom, that’s it, I said and wiped her lips a final time. There’s this foam that gurgles up from their throats and oozes out with the stertorous rattle. They call this the active dying phase.

That phase was over, dead she was, and it’s hard to think past death when you’re smack up against it, so I stepped out to call the nurse, who, the dear, cried a little, produced some papers for me to sign, and then sent me back in:

—I know you’ll want to spend some quality time with mom, she said.

I sat there. Very still. You could feel the room in flat-line. I looked out the window, walked around, and then came to stand over her.

I closed her eyes. (They don’t have to shut simultaneously; that’s dolls.)

I closed the door and got out my cell phone and started taking pictures. I posed Woofie—her stuffed animal sheep dog—alongside her. But after several takes, repositioning him each time, I gave up. Couldn’t get either of them to relax.

What to do. I lifted her out of the bed and gingerly placed her in the arm chair, afraid I’d break her. I let her just lean in it like she didn’t quite want to sit. My idea was to have some sort of tea, though for mom the dainty finger would tangent off a martini.

Tanqueray or Earl Grey, no matter, in sum it’s a unique brew, for I ask you, who among us has fussed around to scratch up an afternoon tea with his just dead mother? It’s never been done—well, maybe Norman Bates in some outtakes somewhere, but in real life? But if somebody doesn’t do it, the universe will be incomplete.

I did jam a chair under the doorknob, for privacy, but then almost immediately I needed it for our tea party. So.

Her gown was open a little. She’d shown me her first mastectomy scar back when she was fifty.

—Here, you want to see?

—I don’t know, not really, mom… but, flip, there it was, a sort of a bar sinister across her chest, smack where I’d rooted for a nipple once. But now, at ninety, there were two slashes—like cancellations when a cartoon critter is knocked out—making her, with her frail rib cage, very lithe and boyish.

Then I did something really weird. I arranged her to sit a little more comfortably, straightened her gown, and began to pat her down. I don’t know what else to call it. I was taking in her whole body, through the palms of my hands. Blotting her in.

One of her eyes had crept open now, as if curious, or maybe to join me finally, and Woofie was flat on his back on the floor looking deader even than she…when the damn door opens.

Enter my nurse, who just stands there and doesn’t withdraw politely and I don’t say ‘Give us a little longer’ or ‘Quality time, you know’, I just keep patting, taking my mother’s measure, feeling her ribs hip bones femurish thighs. Nurse had probably seen it all before anyway, though maybe not; maybe this was a first for her too; at any rate, she didn’t leave.

So, nurse at the door, respectfully watching; Woofie on his back, kick him aside; me feeling up my mom as if this were a reverential thing to do. I squeezed her toes, like a custom hand-grip, and then I was full.

Take my hands if you don’t understand: you can feel it. You’ll need to do it for me someday. Otherwise, the ghost escapes, lost, grieved, nowhere to go. You have to take it in, through the ticklish portals just below where stigmata would be.

As I write this now in my study, one eye in each palm is peeking down at the home keys, Woofie’s perched in his own oblivion behind me on the window seat, and my tea is slowly, ever so slowly getting cold.

[ ]

First published in The Antioch Review, the All Fiction issue. Volume 67, Number 3, Summer 2009, under the title “Wake.” It is further intended for a collection of memoria and kindly ghost stories, Awkward Conversations with the Dead, to which “Mia, This is Phoebe; Phoebe, Mia” in this FLASH section, also belongs.

Endearing and enduring picture of Mom at bottom of Lorelei, in WRITING. Here, about the same time as that cheesecake on the dock, is the happy family, contented dog, felicitous Granddad paintings. Circa 1948, give or take a year. I remember that shirt.

Novitiate

Tip-toeing through the convent after candles snuffed, sipping wisps of novices’ breaths, performing handstands on bosoms’ halos, the thought occurs: Do nuns beat off, removing first their marriage rings?

O, Christ, O, hand of God!